A Kansas City Lawyer Shares His Vision Of Fostering A Love For The Arts

By JOE ROBERTSON

January 25, 2010

The Kansas City Star

Jack Isgur doesn’t meet the people who get his money, so he’s left to wonder if his dream is at work at the end of roads like this. This one leads to Carrollton, Mo., and an English teacher. It splits a winter-gray plain, passing the idle irrigation trusses over snow-patched fields. It crosses the tracks. Passes the closed movie theater, the hoped-for arts center, the courthouse square. Finally, with red-and-black stenciled Trojan logos decorating the asphalt, it reaches Carrollton’s schools and Robin Farias’ class. “What do you carry?” she asks her students. She’d moved in among them, sitting close on a desktop with her feet on the chair. She wants to evoke personal connections in what had been a multisensory introduction to Tim O’Brien’s work of fiction about soldiers in Vietnam, “The Things They Carried.” Girls reach into their purses. Boys thumb through their wallets. Six years ago, Farias earned the first of her three $1,000 scholarships from the Jack J. Isgur Foundation for the Humanities in Education, which focuses on Missouri schools. She was a former travel agent, returned to college, who wanted to teach.

She’s among more than 80 college students since 2001 who successfully completed Isgur’s elaborate application, handled the phone interviews from some of his foundation’s seven board members and earned a financial reward — now up to $1,500 each — that comes from Isgur alone.

“It’s my foundation,” the 73-year-old Kansas City man says. “I fund it.” He worries about young people, especially in rural areas, who might not have good connections to the humanities in financially strained schools that are pressured to produce high math and reading scores — but not art, music, literature or poetry. He remembers himself, not yet a teenager living in Sedalia, Mo., stunned by a magazine picture of an El Greco painting and its wild sky. He bought a print and even found a way to have it framed, not really knowing why, except, “I had to have it.” He remembers his clarinet. His sisters and their piano and violins. He remembers school trips to Kansas City and St. Louis, and staring into the downtown display windows, enjoying the journey itself, thinking, “there’s more to life…”

He worries about what sparks children today and what currents their imaginations run. He answers his concern with his foundation, reaching out for people who have eyes for children in Carrollton, or Mountain View, or Delta, the Bootheel, the Ozarks. The scholarships can’t secure a guarantee that his chosen ones will carry on the mission, but he knows what he wants. “We … want … good … teachers.”

From the end of another road — one that led to Wright City, Mo. — Emily Miesner imagines who Isgur might be. Would he be proud of what she has done here, teaching music to students and watching “the little light in their heads go on”? “I hope to meet him,” she says. If she found him at work, she’d find him in his sparse office as a mostly retired attorney who had made his living practicing personal

injury law. Though he shrugs that off. “I was not getting satisfaction out of it,” he said. Nothing but beige paint colors his walls. No computer, but an electric typewriter. Stacked novels rise over the clutter of his desk.

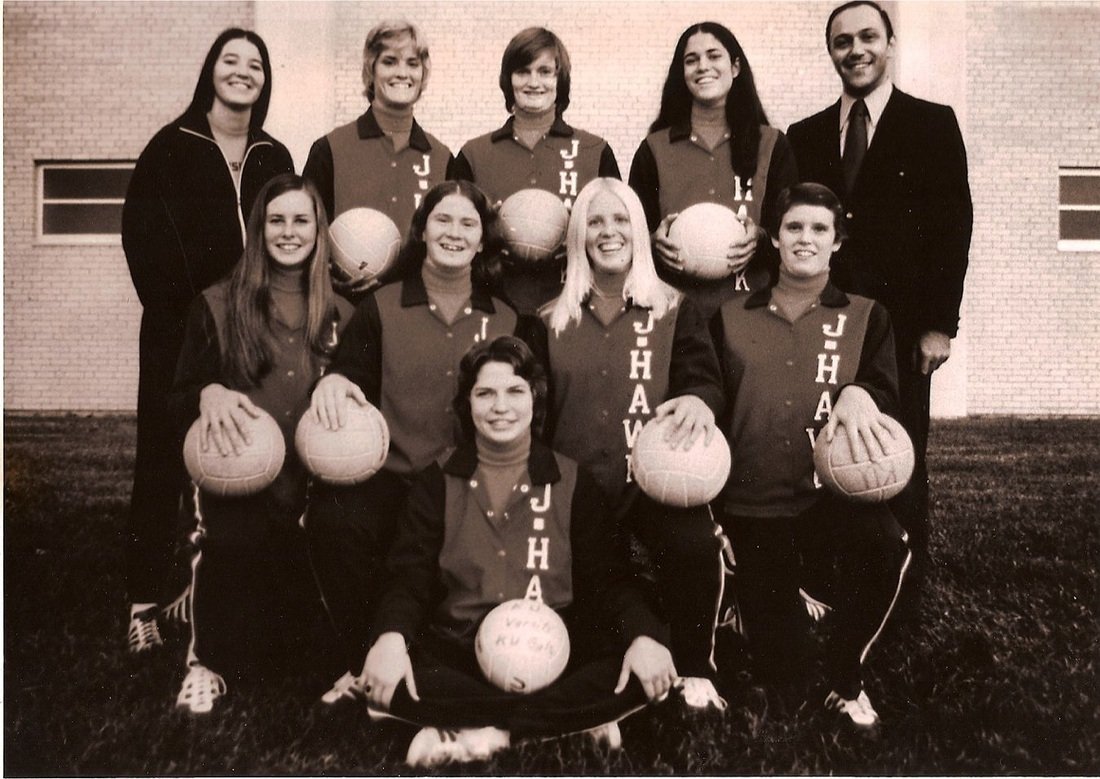

His greater energy went into working with the Boy Scouts and DeMolay, and coaching volleyball. It’s in this other work that he’d become “aware of teenaged thinking,” he said. “Something is lacking. Not with all of them, but some of them.” Friends who were teachers were telling him that the arts were losing in the struggle for support. His nephew’s school had a band, but no orchestra. To neglect the humanities, he said, is to break “the transference” between arts and sciences that fuels both. “You need the creative thinking process,” he said. So he took some accumulated wealth, turned over some stocks and even promised his estate to his foundation to support like-minded and talented teachers. The faces would fill in, but he knew there were children like those in Houston, Mo., who would join the bands that Curtis Tipton would rebuild. He knew there were children like those in Mountain View who needed the songs John Collins would use to bring fifth-grade social studies to life. The arts thrive under inspired teachers, said Michael Bouman, executive director of the Missouri Humanities Council.

Many people lament that the pressures of state tests and the federal No Child Left Behind Act are tying teachers’ hands, he said. “But in my view, policies come and go like changes in the weather,” Bouman said. “What is constant in the education landscape is the human being who can transmit a love of learning despite the weather of the moment. “There are human needs that transcend the times we live in.”

Isgur isn’t expecting professional dancers and novelists to come leaping from his scholarship winners’ classrooms. The spark that Farias struck in students such as Jacob Haygood and Chris Bigby is just as fulfilling. Haygood, 17, is bound for the Air Force when he graduates. Bigby, 16, sees himself in construction.

What they hadn’t been, until Farias got a hold on them, were readers or writers. “She got me straightened out — got me to where I was having fun,” Haygood said. “Reading books, writing poetry.” Bigby has tried his hand at art, drawing scenes imagined from the literature she brought to his class. They live in a town, like any, that needs energy toward the arts, said Karl Marxhausen, a landscape painter who works as a teacher’s aide in the high school. He and other artists have tried special shows to see if there is a climate to support a standing art gallery. A stagnant fundraising campaign to revive a closed movie theater as an arts center needs a boost. “You can live on the backside of nowhere … and see excellent art,” Marxhausen said. “And people say, ‘Wow, maybe something is happening.’ You try again. You get a mailing list. It’s bit by bit.” Schools play a role. Teachers play a role.

Farias figures she felt that long before she wrote about her beliefs in her application for the Isgur scholarship. But her mission is always before her. “It’s always stayed on my mind to bring humanities into my curriculum,” she said. She’s used laminated prints of famous art to inspire short stories. Paper cubes hung by string from her ceiling are mini-autobiographies that the students decorated with words and pictures. If there is going to be an arts center in the old movie theater, they could be the ones to keep it alive.